Despite

many positive aspects, such as the developments in railway travel and

medical equipment, the Victorian era is also often associated with

its negative aspects. While the upper-classes led relatively easy

lives, the lower-class Victorians had to work long hours to barely

keep their families alive. The desire to survive led many people to

commit crimes, as well as many women, like Nancy in Charles

Dickens' Oliver Twist (1837), to prostitution. The large number of

'fallen women' that flooded the streets in the developing cities also

made it an easy environment for individuals, such as the still

unidentified serial killer, 'Jack the Ripper', to murder numerous

women.

|

| The five women believed to be victims of 'Jack the Ripper' |

Types

of crimes and punishment

While

prostitution and drunkenness were a common sight on England's

streets, there were also a number of other crimes being committed.

The Industrial Revolution brought about a number of changes to

manufacturing and transport throughout England between the late 18th

century and early 19th

century. This also caused a change in crime across England's cities,

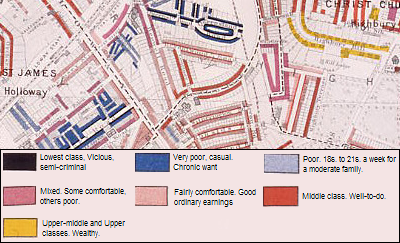

just as the Victorian era was beginning. The growing populations

within cities saw somewhat wealthy,

upper-class citizens living

within relatively close proximity of poor, lower-class citizens, as

can be seen in the portion of Charles Booth's 'London Poverty Map' to

the left, which he created in the late 19th

century in order to study the levels of poverty within London. As a

result of this, there was a dramatic increase in many forms of

robbery

and burglary

being committed against the upper-class citizens.

The

introduction of railway lines across the country also brought a

number of new, petty crimes with it, such as failing to pay to travel

by rail, or acts of vandalism on or around the railway tracks. For

example, using the Old Bailey criminal trial database, I found a case

from 1851 in which two boys, Joseph Gutteridge (Fourteen years old)

and Cornelius Upton (Thirteen years old), were accused of

“feloniously putting a stone upon a certain railway, with intent to

obstruct an engine using the said railway”, of which they were

found guilty. The oldest of the two boys was sentenced to six weeks

confinement, while the younger boy was sentenced to two months

confinement, as the judge considered him “the most blameablet he

having be in an engineer's employment”. Judging by the punishments

they received, attempting to disrupt a train might seem to have been

a quite serious crime, but when you consider the other forms of

punishment the Victorian authorities used, two months in prison does

not seem bad at all.

To

get an idea of how Victorian criminals were punished, I looked at

Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist, which is the story of a

Victorian orphan, who escapes the workhouse where he grew up and

travels to London. There he meets Fagin and his pickpockets and falls

in to a life of crime, before being rescued by an upper-class

gentleman, Mr. Brownlow. Dickens' novel sees a number of characters

punished for the crimes they commit throughout, three of which are

punished in ways that were commonly used in 19th century

society. The first is the Artful Dodger, a skilled pickpocket who

steals for Fagin, who is sentenced to go “abroad for a common

twopenny-halfpenny sneeze-box” (405). Dickens' is referring to

transportation, which was a common punishment up until 1857, where

the criminal would be sent away from Britain to serve their sentence.

Next we have Fagin, who takes children off of the streets and trains

them to steal for him, who is sentenced “to be hanged by the neck,

till he was dead” (500). Hanging was, although the most severe form

of punishment, still commonly used to punish for a number of serious

and, what we may now consider, minor offences. Finally, the reader is

told of the fate of Monks (Oliver's evil half-brother), who moved to

America after the events of Dickens' story, where he “fell into his

old courses […] and died in prison” (507).

19th

century prisons

When

Charles Dickens was aged just 12, his father, John Dickens, was

imprisoned for 3 months in the Marshalsea Prison for debts he owed to

a baker. As a result of these money troubles, his wife and three of

their children, including Charles, also had to move in to Marshalsea.

If you have read Charles Dickens' Little

Dorrit, which heavily

features the Marshalsea Prison, it will be clear to you that the 3

months that he spent at the prison made a lasting impression on him.

However, Dickens' descriptions of the cells inside the Newgate Prison, within Oliver

Twist, will provide you

with a more precise idea of what it would have been like to have

occupied a Victorian prison cell. Dickens writes that the “cell was

in shape and size something like an area cellar, only not so light.

It was most intolerably dirty” (86). But are Dickens' descriptions

accurate? Judging by the image below, Dickens had a clear idea of

these things.

|

| A Victorian prison cell taken from the 'Wellclose Prison', now on display at the Museum of London |

A

“cube 7 feet by 12, with a barred window of ground glass at one

end, and a black painted door at the other” (27), Frederick

Brocklehurst, a member of the then newly formed Independent Labour

Party, describes in Philip Priestley's book, Victorian

Prison Lives, English Prison Biography 1830-1914.

If you wish to learn of the experiences of Victorian prisoners

directly from the prisoners themselves, then Priestley's book is a

good place to start.

The

Victorian prison system was based on the ideas of two individuals,

Sir Joshua Jebb and Sir Edmund DuCane. Early in the Victorian period,

Jebb began to advocate the 'separate' approach, which “located

prisoners in individual cells where they were held in strict solitary

confinement. Reform was to be brought about by the influences of

solitude, prayer, simple work, and the ministrations of sober,

upright and god-fearing attendants” (6). However, it was found that

this method of rehabilitation often drove prisoners to madness and

failed to produce the desired changes. DuCane designed an approach to

rival this, which was referred to as the 'silent' system, where

prisoners were “kept in solitude at night but allowed to congregate

during the day, in strictly enforced silence, for work and worship”

(6).

The

prison routine was simple. According to Arthur Griffiths, who was the

assistant deputy governor at Chatham prison in during the 1870s, “The

first bell to rouse out the convicts was at 5.30 a.m.” (82). At

6.30 the doors were unlocked for inmates to empty their slop-buckets

and fill their water cans before breakfast. They would then be

required to take part in up to an hour of exercise. At 8.30 the

prisoners would head to the chapel, whether they believed in

Christianity or not, as Henry Harcourt found out in 1864 when he

attempted to worship something other than the permitted Church of

England, Roman Catholic or Judaism beliefs. They would then go about

their 'hard labour', which could have been a number of tasks, from

restoring old rope, to sewing coal-sacks. I bet they couldn't wait

for their dinner of, in the words of Frederick Brocklehurst,

“brown-to-black bread and […] 'stirabout'” (151).

|

| Stirabout: a mixture of meat, potatoes, oatmeal and onions |

Works cited

-

Dickens, C. Oliver Twist.

London: Penguin popular classics,1994.

-

Priestley, P. Victorian

Prison Lives: English Prison Biography 1830-1914.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

-

Museum of London. Prison

Cell. 11 November 2013

<http://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/Online/object.aspx?objectID=object-497829>

-

Old Bailey Online. Joseph

Gutteridge, Cornelius Upton, Damage to Property.

1851. 11 November 2013

<http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t18510818-1660-offence-1&div=t18510818-1660>

-

National Archives. Crime

and Punishment. 11

November 2013 <http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/candp/>

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteA very descriptive work on crime and punishment. Though the crowded streets of England was a market place for criminals, you tell us that characters in 'Oliver Twist' get punished for their wrongdoings. The crowded streets gave these criminals space to perform, yes, however in 'Oliver Twist' we see that criminals experience death penalties, which also builds the moral of the book. Your example about railway crimes is something I think we can empathise with today; often passengers are caught without oyster cards and likewise which they are fined for. Very nice to read your blog.

ReplyDeleteMy husband Left me after years of our marriage, He started the spiritual prayer on my husband, and gave me so much assurance and guaranteed me that he was going to bring my husband back to my feet in just 48 hours of the prayer. I was so confident in his work and just as he said in the beginning, my husband is finally back to me again, yes he is back with all his hearts, Love, care, emotions and flowers and things are better now. I would have no hesitation to recommend him to anybody who is in need of help..Robinson.buckler@yahoo.com…...................

ReplyDeleteThanks again,

Ottawa, Canada