|

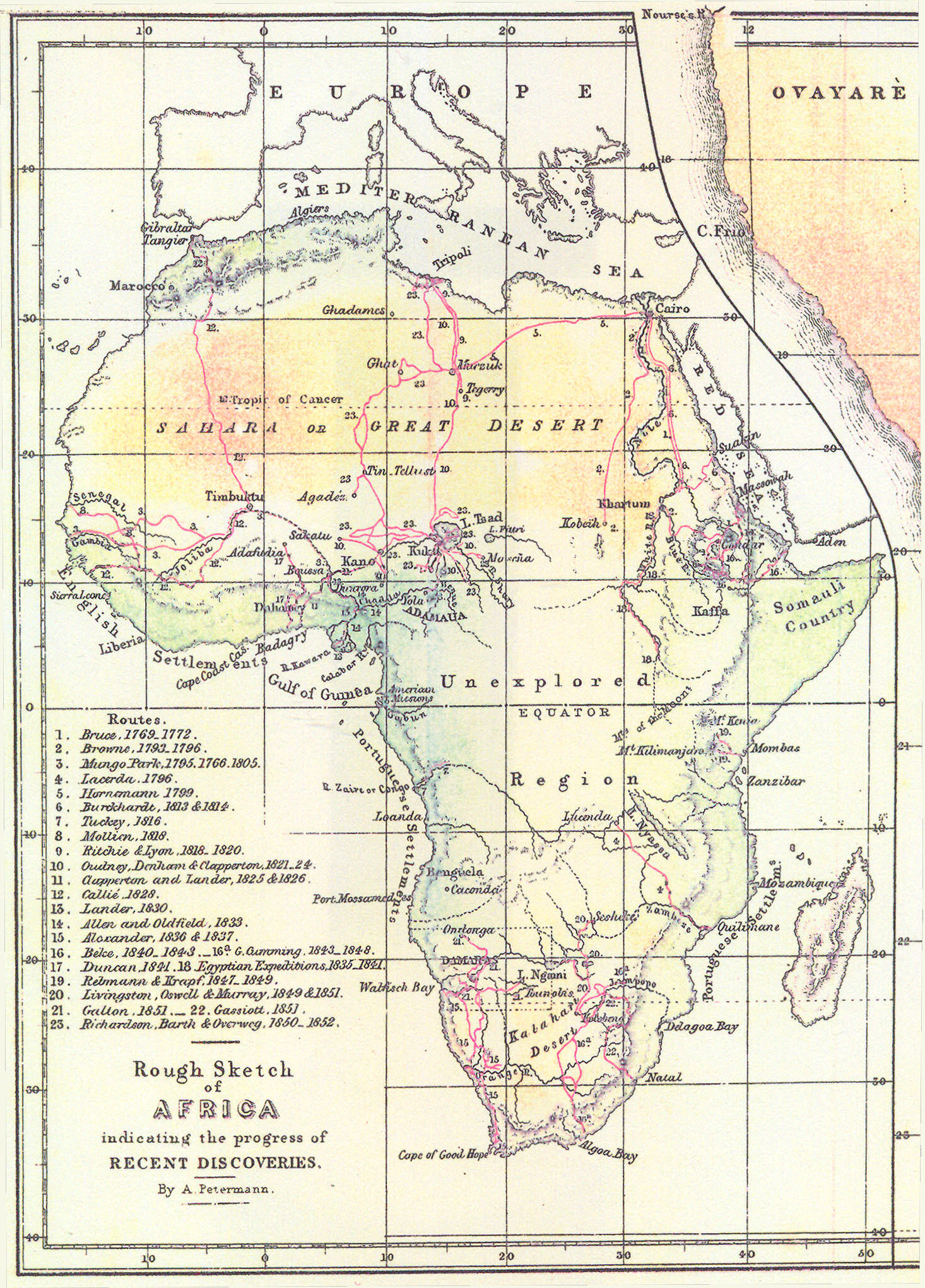

| "Rough Sketch of Africa indicating the progress of recent discoveries" by the famous cartographer August Heinrich Petermann, 1853. The middle of the continent is simply named the "Unexplored Region". |

By the mid-nineteenth century, much

of the world had been, for the most part, already claimed and discovered. However, as we "journey" through the latter half of the

nineteenth-century, we begin to see a flourish of exploration in Africa, more

specifically the "dark heart of Africa" - which remained one of the

last undiscovered areas in the world during this period (along with the Arctic

and Antarctic regions). It was left to explorers such as David Livingstone,

Henry Morton Stanley, and Frederick Selous to discover this last region of

Africa, which was achieved by the 1870's.

So the exploration of Africa was occurring

during the mid-to-late Victorian period. What then, you might ask, does this

have to do with Victorian culture and society? Well reader, you will take

immense interest in knowing it has everything to do with Victorian

society. The Victorians didn't just take an interest in these vast expeditions

to otherworldly, unexplored places. They were obsessed with them (no

really, they were.) One of the ways we can see this is through looking at the literature

that was produced during this 50-year period. There begins an astounding

resurgence of adventure fiction (largely geared towards boys and young men,

but more on that later) and the creation of the "lost world" genre,

with texts such as Rudyard Kipling's The Man Who Would Be King and H.

Rider Haggard's King Solomon's Mines, being published. Solomon's

Mines, interestingly, is largely considered to be the first novel in the

"lost world" canon, and deals with the discovery and exploration of

the "heart of Africa". Indeed, the British southeast African

explorer Frederick Selous inspired Rider’s protagonist of his novel, Allan

Quatermain (who in turn was the inspiration for the eponymous character in the

popular Indiana Jones film series).

It is not difficult to understand why King Solomon’s Mines, was so immensely

popular with the Victorians. A novel concerning the discovery of the ancient

world would have appealed greatly to them due to their large obsession with

time and history. Indeed, John Stuart Mill argued that “The idea of

comparing one’s age with former ages, or with the notion of those which are yet

to come, had occurred to philosophers; but it never before was itself the

dominant idea of any age.” (‘The Spirit of Age’, 1831). The Victorian reader is almost instantly hooked

at the mention of an ancient settlement laden with beautiful gems and worldly

riches. Just like the real-life explorers journeying to discover unclaimed

land, there is something enthralling about an unknown space; “‘Solomon’s Mines?’”

ejaculated both my hearers at once. ‘Where are they?’ ‘I don’t know’ I said; ‘I

know where there are said to be. Once I saw the peaks of the mountains that

border them, but there were a hundred and thirty miles of desert between me and

them, and I am not aware that any white man ever got across save one.’” (King Solomon's Mines, 10).

Perhaps it is the notion of freedom and independence that an unclaimed space

can provide. We certainly see this in other Victorian adventure novels - R.L

Stevenson’s Treasure Island for

example - and there are many similarities between both Stevenson’s novel and Solomon’s Mines. They both are told from

a first person narrator, who inhibits a casual, conversational approach in

narrating their “journey” to the reader. Another similarity between these texts

is their use of maps within the novel. This use of verisimilitude further

enhances the idea of real-life exploration, and increases the interest the

reader has through reading these lost-world, adventure novels. If young Jim

Hawkins and old Allan Quatermain can explore new worlds and discover “money to

eat – to roll in – to play duck and drake with ever after” (Treasure Island 34), why couldn’t

they?

|

| Map of Treasure Island, published in the first edition of the text and drawn by Stevenson himself. |

|

| The Way to Kukunaland as featured in King Solomon's Mines. Notice the similarities between this map and the map of Treasure Island. |

While it is true that famous explorers such as

Stanley and Solous inspired these novels, it is worth considering how they in fact inspired future explorers to be adopt the role of the "hero" in society. (In other words, they became a "celebrity" in Victorian England, equivalent to the countless film stars society obsesses over today). As is often the case, the explorer in literature

is the protagonist and the hero, and these brave, tough explorers would have

been very aware that Britain viewed them in a similar light. Henry Morton

Stanley, for instance (most famous for his extensive exploration of central

Africa and finding the then missing David Livingstone in 1869), was incredibly aware of the

fame and fortune waiting for him in Britain because of his discovery and

exploration. For many Victorians, he represented a real-life version of these

literary heroes that were so immensely popular during the Victorian period. One

only has to look at through the John Johnson collection to discover all the advertisements

and merchandise associated with Stanley and his travels. The image below

“Stanley’s Expedition to Relieve Emin Pasha” shows the African natives carrying

Huntley & Palmers biscuits on their head, while Stanley looks ahead, merely

watching them. Clearly intended to be an advert for the biscuit company, I

think it represents much more. Regardless of Stanley’s success in the riches he

finds whist exploring, he is aware of the riches he has waiting for him at

home, and he merely treats these natives and the new places he discovers as

“fool’s gold”, aware that, for him at least, it holds no true value, and that

his money lies in merchandise and advertisements in Britain, where he can be

treated as a “hero”.

|

| 'Stanley's Expedition to Relieve Emin Pasha' - taken from the John Johnson collection. Does this image represent heroism by Stanley or it is simply a money-making advertisement for him? |

What do all the explorers (both real and

fictional) have in common? That’s right, no women. This was to be expected

during the Victorian period; it is interesting to note that both in Treasure Island and King Solomon’s Mines, women are (mostly) conspicuously absent. (Stevenson

often stated that Treasure Island was

to be “a story for boys…women were excluded”). Several blogs have discussed in detail many of the difficulties

women faced during the Victorian period, and unfortunately just like those, the role of the explorer was not for the woman; men dominated the field of

exploration. Perhaps this is because of the ceremonialism of exploring new land

for Britain, as women were considered unequal during this period. If a woman

were to claim land for Britain it would not have held the same worth or

value.

The exploration of Africa captivated the

Victorian audience, just as the 21st Century has developed an

obsession with space exploration. The yearning for discovery and new places

seems to be ingrained in society. The question is: where will it take us next?

Works Cited:

Images:

"Rough Sketch of Africa

indicating the progress of recent discoveries" - http://www.abelard.org/galton/galton3.php

Map of Treasure Island - http://15menonadeadmanschest.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/treasure-island-by-robert-louis.html

The way

to Kukunaland - http://www.cleavebooks.co.uk/grol/haggard/ksmine02.htm

‘Stanley’s Expedition to Relieve

Emin Pasha’ - http://johnjohnson.chadwyck.co.uk/search/displayItemImage.do?&&PageNumber=1&FormatType=fulltextimages&shelfNumber=1&ResultsID=1494F2886621C09CCA&ItemNumber=8&ItemID=20090219103027kg

Texts:

Haggard, Henry Rider and Dennis

Butts. King Solomon’s Mines. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2008. Print.

Stuart Mill, John. ‘The Spirit of

the Age’, 1831.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Treasure Island. New York: Penguin

Books, 2003. Print.

Wow Daniel, this is amazing! Your links and supportive quotes for your analysis are great!

ReplyDeleteGreat post! Very informative and the images you chose really link to what you're saying!

ReplyDeleteThank you Lizzie and Bianca. I'm glad you enjoyed reading about the exploration of Africa and I would definitely recommend you ready King Solomon's Mines - a thoroughly enjoyable read that gives you a completely new perspective on the importance of these kinds of expeditions during the mid-to-late Victorian period.

ReplyDeleteI was diagnosed with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) four years ago. For over two years, I relied on prescription medications and therapies, but unfortunately, the symptoms continued to worsen. My breathing became more laboured, and I experienced increasing fatigue and shortness of breath with even minimal activity.Last year, out of desperation and hope, I decided to try an herbal treatment program from NaturePath Herbal Clinic.Honestly, I was skeptical at first, but within a few months of starting the treatment, I began to notice real changes. My breathing became easier, the tightness in my chest eased, and I felt more energetic and capable in my daily life. Incredibly, I also regained much of my stamina and confidence. It’s been a life-changing experience I feel more like myself again, better than I’ve felt in years.If you or a loved one is struggling with IPF, I truly recommend looking into their natural approach. You can visit their website at www.naturepathherbalclinic.com their email info@naturepathherbalclinic.com

ReplyDelete