After a

five minute walk from Borough tube station, I found myself standing before two

iron gates and a small plaque on a wall. This bleak scene is all that remains

of Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison. Glancing up at the brick wall and the spiked

gates, I imagined the misery and solitude they caused for people some 200 years

before. The story of Little Dorrit

(1857) by Charles Dickens came to mind as

I imagined the life of one born into this prison environment with no hopeful

prospect of leaving. I recalled a description of these very gates used by

Dickens in the text: “the gate jarred heavily and hopelessly […] With the

funeral clang that it sounded into Arthur’s heart, his sense of weakness

returned” (720). My trip to Marshalsea made me consider what life was like for

those who were detained behind these gates and the impact they had for those on

the outside.

|

| Figure 2. Iron Gates of Marshalsea - Outside the Prison |

|

| Figure 1. Iron Gates of Marshalsea - Inside the Prison, "in the shadow of the Marshalsea wall" (Little Dorrit, 250) |

|

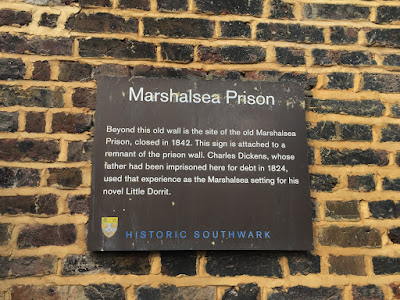

| Figure 3. Sign by the Marshalsea Gates |

|

| Figure 4. Sign on Footpath outside Marshalsea Gates |

|

| Figure 5. Little Dorrit Court SE1 |

Victorian Debt

The

Victorian era was rife with poverty and devastation. From workhouses, child

labour and slums to crime, prostitution and disease the era was overwhelmed

with misery for the working class. With these desperate conditions to contend

with, it is easy to see how many people became victims to the cruel debtor

system that dominated the nineteenth century. Low wages meant that people were

unable to afford daily essentials and so they turned to purchasing items

through credit – rather like a modern day bar tab but in bakeries and clothing

shops. These credits were ever-growing and people often found themselves unable

to cope with their arrears. This struggle was common among the working class

and was even transferred into the era’s literature, for instance, in Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) by Mary

Elizabeth Braddon. Mrs Vincent fled her home as she could not afford to pay her bread

charges. The local baker said: “That lady owes me upwards of eleven pound for

bread, and it’s rather more than I can afford to lose” (181). Debt was

devastating and not only meant you had “slipped down to the depths or

degradation and disgrace” (Little Dorrit,

681) in society, but it also meant that you ran the even greater risk of being

sent to a debtors’ prison – a threat that chilled any Victorian to the bone.

Escaping this dreadful fate was near impossible. Some Victorians even resorted

to suicide, for example, Mr Merdle in Dickens’ Little Dorrit, who killed himself with a penknife to avoid the

traumatic consequences of bankruptcy. Jerry White comments on this link between

Victorian debt and suicide: “Debt was the stuff of nightmare […] A cut-throat

razor was the shortest way out of Queer Street. No wonder indebtedness was such

a prominent theme in nineteenth-century fiction, especially the novel set in

London” (216). People contended with extremes in order to escape their arrears.

However, for those left with no alternative, their only option was the cold,

hard world behind the iron gates.

Marshalsea: A Place of Mental and

Physical Detainment

|

| Figure 6. Instruments of Torture used on Marshalsea Prisoners, 1729 |

Marshalsea,

1373-1842, was one of the four main debtors’ prisons that were active in London

during the nineteenth century. The Bankruptcy Act of 1869 – “An Act for the

Abolition of Imprisonment for Debt” (62) – prevented people from being

imprisoned for minor fees, however, before this act was passed creditors were

free to send their debtors to prison for any sum of money, large or small. Due

to these relaxed guidelines, Marshalsea was overcrowded and congested. As White claims: “these places held about 1,700 prisoners for debt,

though in any year some 7,000 debtors entered their doors” (219). While in

prison, debtors would complete labour work to pay off their arrears

while also paying for their keep within the jail. If unable to afford these

fees, it was not unheard of for inmates to be tortured by the turnkeys,

especially during the eighteenth century. In his novel Little Dorrit, Dickens captures the horrors of life behind the

notorious iron gates through the observations of Little Dorrit herself:

The spikes had

never looked so sharp and cruel, nor the bars so heavy, nor the prison space so

gloomy and contracted. She thought of the sunrise on rolling rivers, of the

sunrise on the wide seas, of the sunrise on rich landscapes […] and she looked

down into the living grave on which the sun had risen (220).

|

| Figure 8. Behind the Marshalsea Wall - Inside the Prison |

|

| Figure 7. "Part of the Site of Marshalsea Jail, London" by Francis Hopkinson Smith |

Antithesis

in this passage weighs heavily upon the reader’s mind. The bright imagery of

the naturalistic sunrises contrast sharply against the “gloomy” and dark

“prison space”. Repetition of the phrase “so” amplifies the harsh conditions

allowing one to imagine the daunting atmosphere within Marshalsea’s walls;

inside the “living grave”. Through this quote, readers can wonder at Dickens’

feelings towards Marshalsea. By contrasting the pastoral sunrises against the

confining prison gates, Dickens may be suggesting that these prisons are

unnatural and avoidable. Amy Dorrit’s questioning tone causes us to wonder at

the benefits of this establishment: “‘It seems to me hard,’ said Little Dorrit,

‘that he should have lose so many years and suffered so much, and at last pay

all the debts as well. It seems to me hard that he should pay in life and money

both’” (397). Amy’s logic is practical and provides an insight into the flawed

Victorian legal system. Dickens, therefore, appears to be openly interrogating

the benefits of Marshalsea and querying the humanity of the unnatural system.

|

| Figure 9. Iron Gates of Marshalsea - Remains of Prison Entrance. The space "between the free city and the iron gates" (Little Dorrit, 77) |

Dickens

also captures the mental torture of life “in the shadow of the Marshalsea wall”

(250). In the latter portion of the novel, when Arthur is imprisoned, the

narrator writes:

|

[A] burning

restlessness set in, an agonised impatience of the prison, and a conviction

that he was going to break his heart and die there, which caused him

indescribable suffering. […] The sensation of being stifled sometimes so

overpowered him, that he would stand at the window holding his throat and

gasping (713).

|

Marshalsea, Charles Dickens and Little Dorrit

Despite

the negative descriptions of Marshalsea used by Dickens, it is often described

as ‘home’ by Amy. For instance, when she is talking to Arthur in

Chapter 22: “‘Don’t call it home, my child!’ he entreated. ‘It is always

painful to me to hear you call it home.’ ‘But it is home! What else can I call

home?’” (249). It is possible that Little

Dorrit is semi-autobiographical. The novel was published serially between

1855-1857, but was set “thirty years ago” (5) when Dickens was a child himself.

During his childhood from February – May 1824 his father, John Dickens,

was imprisoned in Marshalsea as he owed James Kerr, a local baker, £40 and 10

shillings. David Rowland comments: “That was certainly a very large debt; these

days that is roughly the equivalent to the sum of some, £3,110” (Old Police

Cells Museum).

|

| Figure 11. John Dickens, prisoner at Marshalsea, 20th February 1824 |

While his family lived in

Marshalsea, Charles, aged twelve, was forced to work in a blackening

factory and live completely independently. During these months, perhaps the jail was the only connection he

had to a “home” as that was where he could find his family and seek refuge from

the working world. Perhaps “The Father of the Marshalsea” (58) was actually

Dickens’ ‘Father at the Marshalsea’.

Thus, we wonder whether Dickens’ negative associations and criticisms of the prison are a direct result of his childhood sufferings and his father’s imprisonment.

|

| Figure 12. Inscription on the Floor |

I

conclude that the world behind the iron gates of Marshalsea was one of physical

and mental torment, both for the “faded crowd [the gates] shut in” (69),

such as, Mr Dorrit or John Dickens, and for those living outside who were forced

to deal with the consequences, for instance, Little Dorrit and Charles Dickens

himself.

Work

Cited:

Bankruptcy

Act 1869,

Victoria. Chapter 62. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1901. Web. 02 March

2016.

Braddon, M. E. Lady Audley’s Secret. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions,

1997. Print.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions, 1996.

Print.

Dickens, Charles. The Pickwick Papers. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions,

1993. Print.

Hayward, A. L. The Days of Dickens. Hamden, Coun.: Shoestring Press Inc, 1968.

Print.

Rowland, David. Old Police Cells Museum. Marshalsea Prison, London. {The Governor

Indicted for Murder}. 2014. Web. 02 March 2016. <http://www.oldpolicecellsmuseum.org.uk/page/marshalsea_prison_london>

White, Jerry. London in the Nineteenth Century. London: Jonathan Cape, 2007.

Print.

Images

Cited:

Figure 1. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Iron Gates of

Marshalsea – Inside the Prison”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 2. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Iron Gates of

Marshalsea – Outside the Prison”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 3. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Sign by the Marshalsea

Gates”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 4. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Sign on Footpath

outside Marshalsea Gates”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 5. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Little Dorrit Court

SE1”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 6. British History Online. “Instruments of

Torture in the Marshalsea, 1729”. British

History Online. 1955. Web. 06 March 2016. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol25/plate-5>

Figure 7. Smith, F. H. “Part of the Site of Marshalsea

Jail, London”. Project Gutenberg.

2008. Web. 06 March 2016. <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/27340/27340-h/27340-h.htm>

Figure 8. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Behind the Marshalsea

Wall – Inside the Prison”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 9. Bialkowski, Phoebe. “Iron Gates of

Marshalsea – Remains of Prison Entrance”. 2016. JPEG File.

Figure 10. British History Online. “The South Side of

the North Front of Marshalsea, 1773”. 1955. Web. 06 March 2016. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol25/plate-5>

Figure 11. Who Do You Think You Are?. “John Dickens,

father of author Charles Dickens, was taken to Marshalsea in 1824 for falling

in debt to a local baker (Credit: The National Archives)”. 2014. Web. 06 March

2016. <http://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/news/weekly-round-debtors-prison-records-revealed-online>

Phoebe, I really think you hit on some interesting points and talked about them thoroughly - it was a great read! I do agree with you, I think Charles Dickens was greatly affected by his stigmatised childhood as a result of his father's debts and this - without a doubt - influenced his writing of Little Dorrit. Your comparative pictures are great and the remains of Marshalsea offer today's Londoners with a reminder of the reality of debt and its consequences in Victorian Britain.

ReplyDeleteHi Sarah,

DeleteThank you for your comments on my blog. I thoroughly enjoyed researching the post and discovering more about the history of London - events that occurred virtually on our doorsteps!

I would definitely recommend you go and visit the prison's remains. They're hidden away in a little park but they have so much importance and weight in our cultural history!

Phoebe

Hi Phoebe,

ReplyDeleteWhat an engaging read. I found the details you provided of John Dicken's debts and imprisonment particularly fascinating -- and I wonder what he was buying at the baker's to rack up £3000 of debt! This blog deepened my understanding of many of the issues discussed in Victorian texts, and the fear that many lower-income families lived in. I wondered if you'd come across details of debtor's prisons in other parts of Britain? London debtor's prisons are notorious, but reports of them in other parts of the country seem much rarer.

Alastair

Hello Alastair,

DeleteI'm glad you enjoyed reading my blog.

I decided to focus my attention on the notorious Marshalsea due to it's connections to Dickens and his infamous Little Dorrit. London debtors' prisons were by far the largest and detained the most inmates, however, I also discovered that smaller prisons were set up around the country. In more rustic areas, debtors were even held in village-lock ups and castle cellars. Have a look here: http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/laworder/policeprisons/overview/earlyprisons/

Hope that helps to answer your question.

Phoebe

Hey Phoebe,

ReplyDeleteYour blog was a pleasure to read and very insightful. Very well researched and really did deepen my knowledge and I think I will most likely be going to visit the place myself.

Suhaama

Hi Suhaama,

DeleteThank you for your comment. I'm glad you enjoyed my post :)

Phoebe

What a Awesome Post and great article to Iron Gates, Thanks author your Awesome tropic and Excellent Content. Truly I got very Valuable information here. Security Gates

ReplyDeleteI started on COPD Herbal treatment from Ultimate Health Home, the treatment worked incredibly for my lungs condition. I used the herbal treatment for almost 4 months, it reversed my COPD. My severe shortness of breath, dry cough, chest tightness gradually disappeared. Reach Ultimate Health Home via their website at www.ultimatelifeclinic.com I can breath much better and It feels comfortable!

ReplyDelete