In

today’s society, words such as ‘soul mate’ and ‘soulless’ are used anecdotally,

however the soul has wider resonances in the Victorian period. It was a time of

transformation and progression, which also meant that the Victorian views on

the soul were constantly changing. People believed in the soul for various reasons

and usually the belief itself was different.

For

some Victorians the soul meant that there was life after death and that the

soul could live on. For others, it was the belief that the soul could stay on

earth in the form of a ghost to haunt the living. Others believed that the soul

could connect two people forever; this is similar to the modern use of the word

‘soul mate.’ The soul was the key to having lifelong, unbreakable connections.

Another interesting view the Victorians had on the soul was that they wanted to

maintain parts of the soul on earth, the belief that the immaterial could

become materialised.

Despite

the progress in science and technology, the Victorians were overwhelmed by the

paranormal and the supernatural. ‘In

the late Victorian era, a great number of people admitted to have communication

with ghosts.’ (Victorian Spiritualism, Dr Andrzej Diniejko, 14 November 2013). This indicates that the Victorians were

intrigued by the idea of being able to communicate with the souls of the

departed.

(Charles Demuth Oil Painting)

Above is a painting illustrating the moment the governess first sees the

ghost of Peter Quint in The Turn of the Screw.

The artist captures the eerie atmosphere by using the darker tones of the dress

and the pale background. It expresses the ambiguous moment the two worlds; life

and death meet.

Moreover,

some Victorians believed that the soul could live on after death and this

belief brought hope for a sense of immortality. During the Victorian era this idea

had a significant impact on certain writers and their work. Another name for

Tennyson’s renowned poem In Memoriam

was The Way of the Soul. The use of

‘The Way’ creates a sense of direction and could symbolise the soul’s journey. It

was also ‘the way’ for Tennyson to accept Hallam’s death and in some ways to let

go of his soul. The poem deals with death and loss but also reinforces the idea

that the soul can live on after death. Therefore, it became a source of consolation

for most readers at the time. Queen Victoria stated ‘Next to my Bible In Memoriam is my comfort.’

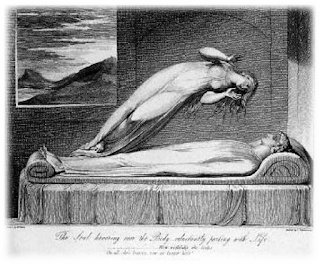

(Soul leaving the body by Schiavonetti 1808)

One of the ways

Tennyson dealt with the loss of his greatest friend was by writing the poem.

Nevertheless, writing about a subject that is so sensitive had other

complications. He writes that he often felt that it was ‘half a sin’ to write

publicly about his grief. ‘To put in words the grief I feel;/ For words, like Nature, half reveal/

And half conceal the Soul within.’ The idea of ‘half reveal’ indicates the

sense of fear he felt for publicly writing about his feelings, which can never

be truly revealed with ‘words.’ Early on in the poem Tennyson writes ‘Our

little systems have their day’ which suggests that life on earth is temporary

and that faith is above science. This is used as evidence to support the idea

that the soul lives on after death and that science does not have to prove

this. Nevertheless during the Victorian era, Dr. Duncan MacDougall attempted to weigh the soul.

The evidence he used to support his hypothesis was that at the moment of death

21 grams were lost, which he believed was the soul departing the body. The two

distinctive observations of the soul show the contrast between science and

faith during the Victorian era.

(Early drafts of a Christmas verse from In Memoriam written out by unknown hand and collected by the Hallam

family, 1833)

The idea of soul mates

and people sharing one soul is explored in Wuthering

Heights. In the novel, Catherine states, ‘I am Heathcliff,’ and after her death Heathcliff

says that he cannot live without his ‘soul.’ This implies that Catherine is his

soul. The idea of two people sharing one soul highlights how important it was

for the Victorians to share lifelong connections even after death. The two

characters are connected by the soul and this makes their connection stronger,

purer and everlasting. This was something, which also reinforced the belief

that the soul can live on after death. Likewise, Heathcliff pleads Catherine’s

soul to ‘haunt’ him when he says, ‘Be with me always - take any form - drive me

mad! Only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you! Oh, God! It

is unutterable! I can not live without my life!’ This gives the soul a sense of

importance. It also shows another perspective the Victorians had on the soul,

which was that it could haunt someone on earth. In Wuthering Heights, Brontë refers to the soul as being omnipotent.

Quote

from Wuthering Heights on a silver

necklace worn in the 21st century. Used as evidence to support that

ideas about the soul from Victorian literature are inspirational to this day.

Victorians were re-imagining lifelong connections after death and sometimes

these connections were imagined in a ‘material’ way. In Digging up the Dead, Burch writes about the life of an 18th

century surgeon, Astley Cooper. In this novel, several questions are raised. Is

the soul only spiritual? Is it material? It states that ‘Someone who spoke of a ‘soul’ or a

‘living principle,’ as meaning a kind of superadded property, was merely being

obscure.’ The word ‘obscure’ informs the reader about the uncertainties behind

the belief of the soul. During the Victorian era, new scientific discoveries

were made and many people started looking for evidence in order to believe in

something or to truly understand it.

Burch also

includes that ‘to suggest that the mind was the function of the brain, that

there was no superadded and invisible quality that could be called a soul, was

certainly a radical idea, and accepting such a materialistic view of life

clearly carried other implications.’ This perspective implied atheism because the

body was something that could be examined but the soul was invisible and some people

refused to believe it existed. The novel also informs the reader about

questions that appeared at the time such as, ‘did the soul – whatever that was

– stay near the body for a while after death, or departed more rapidly? Could

it be damaged by what was done to the body whilst it appeared lifeless?’ People

wanted answers and some were only willing to believe in the idea of the soul if

it was materialised.

(Photograph of a

painting from the Wellcome Collection showing doctors examining a human

skeleton.)

At the Wellcome

Collection in London there is an End of life section, which explores some of

the ways the Victorians kept death in mind. In the book A guide for the incurably curious, it states that ‘the living also

had mementos of the dead, such as death masks and the brooches made from the

hair of the deceased that were worn by Victorian women.’ Similarly, some people

kept small portraits of faces that were half alive and half dead. This again is

evidence to support the way the soul was materialised in the 18th

century. It also illustrated the way the Victorians tried to materialise the

soul as a way of keeping it alive.

In Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and

Culture, Lutz describes the idea of hair jewelry as ‘making of the moment

something permanent.’ This again shows the way the Victorians tried to

materialize the soul and give it a sense of life. By holding on to the lock of hair

indicated the way some Victorians tired to maintain a part of someone who had

died. Therefore, although the Victorians believed in the soul, some also wanted

something in the material form to remind them that the person is dead but their

soul lives on. As stated by Lutz there was ‘a certain approach to the life-death

boundary.’ Lutz also writes how death and the soul had an impact on writers

like Hardy. In Far From the Madding Crowd

the narrator states that ‘immortality consists in being enshrined in others’

memories.’

(Memento mori, locket containing hair. L De Winne © Australian Museum)

Overall, the

Victorians had different beliefs about the soul that were constantly changing.

Evidently, ideas about the soul inspired writers, artists and scientists of the

Victorian era and some ideas remain relevant to this day.

Works Cited

Bibliography

Brontë,

Emily. Wuthering Heights. John Murray ed. N.p.: CreateSpace, 1847.

Print.

Burch,

Druin. Digging up the Dead: Uncovering the Life and times of an

Extraordinary Surgeon. London: Chatto & Windus, 2007. Print.

Kohn,

Marek. A Guide for the Incurably Curious. London: Wellcome

Collection, 2012. Print.

Lutz,

Deborah. Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture. N.p.:

Cambridge UP, n.d. Print.

Tennyson,

Alfred Lord. In Memoriam A.H.H. Paperback ed. Marston Gate:

Amazon.co.uk, n.d. Print.

Images

A

Human Face Half Alive, Half Dead. 18th Century. Wellcome Collection, Italy.

Demuth,

Charles. The Governess First Sees the Ghost of Peter Quint. N.d. Http://www.paintingstar.com/item-the-governess-first-sees-the-ghost-of-peter-quint-illustration-4-for-the-turn-of-the-screw-s118143.html.

Emily

Brontë Silver Necklace. N.d. Etsy. Etsy. Web. 28 Nov. 2015. https://www.etsy.com/listing/125844620/emily-bronte-whatever-our-souls-are-made

Lobley,

John Hodgson. Anatomy Lessons at St Dunstan's. 1919. Wellcome

Collection, St Dunstan's.

Schiavonetti,

Luigi. Soul Leaving the Body. 1808. Belsebuub.com.

The

Papers of Arthur Henry Hallam, including Manuscript Versions of Tennyson's In

Memoriam A.H.H. N.d. British Library. British Library. Web. 28 Nov.

2015. http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-in-memoriam

Winne,

L. De. Memento Mori, Locket. N.d. Australian Museum. Australian

Museum. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

Further Secondary Research

Diniejko,

Dr Andrzej. "Victorian Spiritualism." Victorian Web.

N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

"Duncan

MacDougall (doctor)." Wikipedia, n.d. Web. 28 Nov. 2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duncan_MacDougall_(doctor)

Furneaux,

Holly. "An Introduction to In Memoriam A.H.H." Discovering

Literature: Romantics and Victorians. British Library, n.d. Web. 28 Nov.

2015. http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/in-memoriam

Hi Dimitra

ReplyDeleteI was very intrigued by your blog post as i am interested in the soul and the way Tennyson explores it in In Memoriam. It was a very interested read, and I agree with your findings.

Hi Korie,

ReplyDeleteThank you, I'm glad you liked it! It's nice to receive some positive feedback. I went to the Wellcome Collection for some primary evidence so if you're interested in some ideas about the soul during the Victorian era you could go there.

Dimitra

Hi Dimitra,

ReplyDeleteThe first thing that caught my attention was the title of your post. It is true that today expressions like "soul mates" are used in a very "coloquial way"so I was interested in knowing more about how Victorians used this expression. However, after reading it all I really liked the way you've explained your topic comparing with some books we've read. Also, I am interested in In Memoriam as Koriee said so it was useful to know more about the book.

ReplyDeleteI started on COPD Herbal treatment from ULTIMATE LIFE CLINIC, the treatment worked incredibly for my lungs condition. I used the herbal treatment for almost 4 months, it reversed my COPD. My severe shortness of breath, dry cough, chest tightness gradually disappeared. Reach Ultimate LIFE CLINIC via their website at www.ultimatelifeclinic.com I can breath much better and It feels comfortable!