Paralysis was studied in nineteenth century art, literature,

psychiatry, demonology, medicine, and (pseudo-)sociology. Having no definite

form, and eluding the empiricism of medical treatment, paralysis played on many

of the Victorians’ worst fears. As such, it occupied a prominent position in

the Gothic canon of the era, from the stories of Guy de Maupassant and Edgar

Allen Poe, to the paintings of Henry Fuseli. It was also a topic of ferocious

interest to the scientific community, with pathologists, alienists (an early

(and far better) name for psychiatrists), demonologists and physicians all

vying to prove that the root-cause could be explained through their discipline.

Two kinds of paralysis that horrified and fascinated both camps, were general

paralysis of the insane (GPI), and sleep paralysis. I’ll be tracking this

morbid strand through nineteenth century art, touching upon Maupassant’s death,

Nietzsche’s mental collapse, premature burial, and, of course, Fuseli’s horse.

|

| Fuseli's horse |

GPI

General

paralysis of the insane is defined in the Dictionary of Nursing as “a stage of

tertiary syphilis characterized by dementia and spastic weakness of the limbs.”

However, this syphilitic link wasn’t accepted by Victorians until the 1880s:

prior to this, they considered it a “complication of insanity” (as if

insanity weren’t complicated enough). This assumption, and the name of the disorder, came as a result of the prevalence

of the condition in Victorian asylums. This table shows the severity of

GPI in 1859:

|

| Statistics of deaths in asylums, 1859 |

As can be seen from the percentage of deaths from general paralysis, the mortality rate attributed to the condition was astronomical: as many as 4.65% of patients in asylums in England were dying from GPI. Considering that the highest number of deaths from all other causes was 12.2%, GPI was clearly the primary killer. To make the threat of this incurable, deadly, and elusive disorder even more terrifying to the artists of the era, there was a received wisdom in the nineteenth century that “brain workers” (people who use their brains for work rather than their hands) were more at risk from GPI than others. Studies such as this (below) from 1928, moved to disprove this theory through sociological research into those killed by GPI. As can be seen from the table, the percentage of observed “upper class” (presumably “brain worker”) deaths from the condition was actually lower than the percentage of observed deaths in “skilled workmen” and “unskilled workmen”. While studies like this made it apparent that theories about the increased susceptibility of “brain workers” were nonsense, this sort of research wasn’t carried out until the 1920s. On top of this, a cure wasn’t in sight until the discovery of penicillin in 1928 (which eventually wiped GPI out in developed countries) by which time the condition and the fear surrounding it had produced a profound effect on the arts.

|

| Percentages of deaths by GPI through the classes |

|

| Guy de Maupassant's death certificate |

The

spectre of death-by-paralysis haunted nineteenth-century literature. Guy de

Maupassant, the French short story writer, processed his fears over his

longstanding syphilitic symptoms through his work, which frequently featured

characters suffering with paralytic or cataleptic disorders. This is grimly

prophetic considering Maupassant's death certificate (pictured, left) lists his cause of death as GPI. He was syphilitic for

a great chunk

of his writing career, and experienced hallucinations, migraines, and fits of

paralysis. His short story “Who Knows”, written in 1890, 3 years before his

death, exhibits symptoms of GPI. Luis-Carlos Alvaro pointed this out in his

article on neurological conditions in Maupassant's work: “Maupassant’s

neurosyphilis (GPI) had advanced and its visual and mental symptoms were

clearly developed.”

|

| Guy de Maupassant, and his moustache |

“Who Knows?” follows the mental collapse of its central

character on his return from a night out. He’s walking home when he begins to

hear a “humming noise”. The intensity of this experience steadily escalates

until he sees his armchair “waddling […] through [the] garden”. Alvaro

attributes these descriptions to Maupassant’s experience of migraines,

hallucinations, and “elaborate visual phenomena”, through his accelerating

neurosyphilis. GPI would go on to claim Maupassant’s life; but perhaps the more

threatening aspect of the condition for masters such as Maupassant, was its

capacity to turn the mind against itself.

|

| Friedrich Nietzsche, and his moustache |

Another figure suffered an almost concurrent collapse under

GPI:

Friedrich Nietzsche (lower right), the German philosopher. Nietzsche, although

not considered so in his lifetime, was one of the premier thinkers of the

nineteenth century. A professor of philology by the age of 24, he crammed his

intellectual achievements into a very short career. Like Maupassant, Nietzsche

spent a good chunk of his life with syphilis (also, curiously, both had

magnificent moustaches). This is generally considered to have

developed into GPI, which took his sanity and eventually his life, although

this diagnosis has been challenged by more recent studies. Nietzsche was only

44 when he suffered his initial breakdown in 1889, after which his behaviour

was drastically altered: he spoke to himself and wrote bizarre letters, signing

them as “The Crucified One”. He was admitted to Basel mental asylum in January

1889, before being transferred to Jena, where his condition worsened. He had a

confused concept of his identity, and he repeatedly urinated and soiled

himself, usually proceeding to eat the faeces and drink the urine. He spent the

final years of his life in the care of his family, dying in 1900. Nietzsche’s

decline further demonstrates the fearful prospect that GPI represented to the

genius in the nineteenth century.

Sleep paralysis

|

| Fuseli's The Nightmare |

Sleep paralysis was defined by Samuel Johnson in A Dictionary of the English Language (1755)

as “nightmare”. This definition is played with in the 1781 Henry Fuseli

painting The Nightmare (left). In the

piece, a demon sits astride a sprawled, unconscious maiden (and the eponymous

mare leers behind). This presents fairly accurately experiences of

sleep paralysis; one is accosted in a state of vulnerability by some assailant,

often demonic, who sits astride one, often throttling or otherwise assaulting

the victim. The horse may be peculiar to Fuseli.

Maupassant described a similar experience in his short story “The Horla”:

I sleep ... a long time ... then a dream ... no ... a nightmare lays hold on me. I feel that I am in bed and asleep ... and I feel also that somebody is coming close to me, is looking at me, touching me, is getting on to my bed, is kneeling on my chest, is taking my neck between his hands and squeezing it ... squeezing it with all his might in order to strangle me. I struggle, bound by that terrible powerlessness which paralyses us in our dreams; I try to cry out - but I cannot; I want to move - I cannot; I try, with the most violent efforts and out of breath, to turn over and throw off this being which is crushing and suffocating me - I cannot! And then suddenly I wake up.This is almost an exact reconstruction of Fuseli’s Nightmare (minus the mare). Alvaro interprets this dream as a manifestation of “anxiety bordering on a panic attack”. This both further characterises Maupassant’s experience of neurosyphilis, and points towards a more cultural sickness; the fear over the dormant self. The rise of “alienists” in the medical sphere prompted a growing awareness of the unconscious mind; and with awareness, came fear. What was this uncontrollable segment of the brain up to? Hence, this fear over sleep expressed a fear over the unconscious mind -- linked to another rising fear, over premature burial.

Premature burial

|

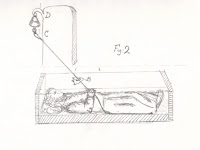

| A diagram showing the function |

|

| An advertisement for a safety coffin |

The word for the fear of being buried alive is Taphophobia,

and in the nineteenth century, it was rampant. There was a thriving trade in safety coffins (left and right), which allowed the cadaver to

signal to those above ground that it wasn’t dead, if it should cease to be so.

There was also a Society for the Prevention of People Being Buried Alive,

founded 1896, and a Hospital for Doubtful Life, opened 1792, where corpses were

kept in warm surroundings until they began to rot. Just to make sure.

Edgar Allen Poe, seizing upon the widespread fear over live

burials, wrote a short horror story called “The Premature Burial” in 1844. In

this story, the narrator recounts a few horrific tales of premature burial,

before revealing that “for several years I have been subject to attacks of the

singular disorder which physicians have agreed to term catalepsy”. Catalepsy is

defined as “a condition of suspended animation”, in which the body can, for

months at a time, assume the appearances of death. The narrator fears that this

condition will lead to his premature burial: “I talked ‘of worms, of tombs, of

epitaphs’”. His fear, however, centres not around the fits of catalepsy that

seize him in his waking hours, but around sleep: “When the nature could endure

wakefulness no longer, it was with a struggle that I consented to sleep – for I

shuddered to reflect that, upon waking, I might find myself tenant of a grave.”

The narrator is not primarily fearful of the deception of his body, but of his

mind; and more specifically, his unconscious mind. The narrative proceeds, with the

narrator taking increasingly paranoid and drastic measures to pre-empt his

premature burial. Eventually, he experiences what he thinks is premature

interment, only to realise after minutes of panic that he is merely sleeping in

a cramped berth on a boat. The horror of thinking that he had been buried alive

causes him to embrace life anew: “I dismissed forever my charnel apprehension,

and with them vanished the cataleptic disorder, of which, perhaps, they had

been less the consequence than the cause.” This demonstrates neatly the

syndrome often expressed in sleep paralysis at the time: fear over the unconscious mind

led to frightening unconscious activity, and a cycle began.

What

GPI, sleep paralysis, and premature burial all prompted, was a fear of the

unknowable. Paralysis negated and resisted both literally and metaphorically

the ceaseless onward-motion of the nineteenth century, and thus occupied a

ghostly space in Victorian art, science, and minds.

Works Cited

Álvaro, Luis-Carlos. "Hallucinations and Pathological

Visual Perceptions in Maupassant's Fantastical Short Stories- A Neurological

Approach."Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 14.2 (2005): 100-15.MedicLatina

[EBSCO]. Web. 30 Oct. 2015.

Bondeson,

Jan. Buried Alive: The

Terrifying History of Our Most Primal Fear. New York: Norton, 2001. Print.

"catalepsy". Dictionary.com

Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 27 Nov. 2015. <Dictionary.comhttp://dictionary.reference.com/browse/catalepsy>.

Hurn, Juliet D. The History of General Paralysis of

the Insane in Britain, 1830 to 1950. Thesis. Thesis (Ph. D.), 1998. N.p.:

n.p., n.d. UCL Discovery.

Web. 30 Oct. 2015. <http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1349281/1/339949.pdf>.

Johnson, Samuel. "Nightmare." A Dictionary of the English

Language. 1755. Johnsonsdictionaryonline.com. Web. 28 Oct. 2015.

<http://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/?page_id=7070&i=1363>.

Martin, Elizabeth A. "General Paralysis

of the Insane." Oxford Dictionary of Nursing. Ed. Tanya A. McFerran. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2014. Oxford Reference

Online [Oxford UP]. Web. 5 Nov.

2015.

Maupassant, Guy

De. Complete Short Stories of

Guy De Maupassant. Garden City, NY: Hanover House, 1955. Print.

Mckinlay, Peter L. "The Proportional Frequency of

General Paralysis of the Insane and Locomotor Ataxia in Different Social

Classes." Journal of

Hygiene J. Hyg. 27.02 (1928):

174-82. PubMed. Web. 27

Oct. 2015.

Orth, M., and M. R. Trimble. "Friedrich Nietzsche's

Mental Illness -- General Paralysis of the Insane vs. Frontotemporal

Dementia." Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica Acta Psychiatr Scand 114.6 (2006): 439-44. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO].

Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

Poe, Edgar Allan. Complete

Stories and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966.

Print.

"taphophobia". Dictionary.com's 21st Century Lexicon. Dictionary.com, LLC. 27 Nov.

2015. <Dictionary.comhttp://dictionary.reference.com/browse/taphophobia>.

Images Used

Brushfield, Mr. An image of Mr Brushfield's Statistics of

Asylums for 1859. Digital image. PB

Works. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Oct. 2015.

<http://victoriancontexts.pbworks.com/w/page/12407425/Mr%20Brushfield%27s%20Statistics%20of%20Asylums%20for%201889>.

Fuseli, Henry. The

Nightmare. Digital image. TeachArt

Wiki. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2015.

<https://teachartwiki.wikispaces.com/The+Nightmare--Henry+Fuseli>.

Image of an

advertising flier for safety coffin. Digital image. Grave Matters. N.p., n.d. Web.

20 Nov. 2015. <http://www.marjoleinplatjee.com/2015/08/>.

Image of Guy de Maupassant's death certificate. Digital

image.Allposters.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 Nov. 2015.

<http://www.allposters.com/-sp/Death-Certificate-of-Guy-De-Maupassant-1850-93-7th-July-1893-Detail-Posters_i10073544_.htm>.

Image of sketch of

safety coffin operation. Digital image. Gothic.life.

N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

<http://gothic.life/why-victorians-had-bells-on-their-graves/image/1/>.

McKinlay, Peter L. Cropped image of table from journal

article. Digital image.NCBI. PMC, n.d. Web. 3 Nov. 2015.

<http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2167761/?page=5>.

Unknown. Image

of 1883 photograph of Guy de Maupassant. Digital image.Exilio. N.p.,

n.d. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

<http://exilioss.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/guy-de-maupassant-18501893.html>.

Unknown. Image of photograph of Friedrich Nietzsche. Digital

image.Dasein.is. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

<http://dasein.is/nietzsche/>.

Bibliography

Adler,

Shelley R. Sleep Paralysis:

Night-mares, Nocebos, and the Mind-body Connection. New Brunswick, NJ:

Rutgers UP, 2011. ProQuest

Ebrary. Jan. 2011. Web. 15 Oct.

2015.

Andrew

Roberts. "Mental Health History 1842-1844." Andrew Roberts' Web Site. N.p.,

n.d. Web. 27 Oct. 2015.

<http://studymore.org.uk/4_13_ta.htm>.

Frenzel,

Ivo, and Joachim Neugroschel. Friedrich

Nietzsche: An Illustrated Biography.

New York: Pegasus, 1967. Print.

Hide,

Louise. "Making Sense of Pain: Delusions, Syphilis, and Somatic Pain in

London County Council Asylums, C. 1900." Interdisciplinary Studies in

the Long Nineteenth Century 0.15

(2012): n. pag. Open Library

of Humanities. Web. 20 Oct. 2015.

Hirsch,

Harold L., and Lawrence E. Putnam. Penicillin.

New York: Medical Encyclopedia, 1958. Print.

Lerner,

Michael G. Maupassant. New York: G. Braziller, 1975. Print.

McDowall,

T. W. "Trephining Followed By Drainage

Of The Subarachnoid Space In General Paralysis Of The Insane." The British Medical Journal2

(1893): 462-63. JSTOR [JSTOR].

Web. 28 Oct. 2015.

Myrone,

Martin. Gothic Nightmares:

Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination. Ed. Christopher Frayling and Marina Warner. London: Tate,

2006. Print.

Wolf,

Peter. "Epilepsy and Catalepsy in Anglo-American Literature between

Romanticism and Realism: Tennyson, Poe, Eliot and

Collins." Journal of the

History of the Neurosciences 9.3

(2000): 286-93. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO]. Web. 27

Oct. 2015.

Further Reading

On GPI:

For an

overview, see: "General Paresis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia." U.S National Library of Medicine.

U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 2015.

<https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000748.htm>.

For more

information on medical knowledge of the disorder in the context discussed in

this blog, see this from 1904: Kraepelin, Emil. Lectures on Clinical Psychiatry.

New York: Hafner Pub., 1968. Print. (See in particular lectures V, X, XII, and

XX for GPI).

For a

more detailed insight see from 1886: Mickle, William Julius. General Paralysis of the Insane.

London: Lewis, 1886. Print.

Or find

online at: Mickle, William Julius. "General Paralysis of the Insane." General Paralysis of the Insane.

Internet Archive, <https://archive.org/stream/generalparalysi00mickgoog#page/n14/mode/2up>.

On sleep paralysis:

For

analysis in literary/psychoanalytical contexts see: Schatz, Stephanie L.

"Between Freud and Coleridge: Contemporary Scholarship on Victorian

Literature and the Science of Dream-states." Literature Compass 12.2 (2015): 72-82. Academic Search Premier [EBSCO].

Web.

For studies of sleep

disorders/paralysis in Dickens, see: Greaney,

Michael. "Sleep and Sleep-watching in Dickens: The Case of Barnaby

Rudge." Studies in the

Novel 46.1 (2014): 1-19. Project MUSE [Johns Hopkins UP].

Web.

For a more modern, cultural study, see: Hinton, D. E. "Culture and Sleep Paralysis." Transcultural Psychiatry 42.1 (2005): 5-10. Sage Journals. Web.

On premature burial:

For an essay on Poe’s tale see: Forbes, Erin. "From Prison Cell to Slave Ship: Social

Death in 'The Premature Burial'" Poe

Studies 46.1 (2013): 32-59. Project MUSE [Johns Hopkins UP].

Web.

For analysis of the fear in general, see: Wojcicka, Natalia. "The

Living Dead: The Uncanny and Nineteenth-Century Moral Panic over Premature

Burial." Styles of

Communcation 2010.2 (2010):

176-87. Academic Search

Premier [EBSCO]. Web.

For Victorian literature that discusses

paralysis:

Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. London:

Vintage, 2012. Print.

Collins,

Wilkie. Man and Wife. Ed.

Norman Page. London: Oxford UP, 1995. Print.

Corelli, Marie. The Sorrows of Satan, Or, The

Strange Experience of One Geoffrey Tempest, Millionaire: A Romance. Oxford:

Oxford UP, 1996. Print.

Craik,

Dinah Maria Mulock. John

Halifax, Gentleman: With an Introd. by Robin Denniston. Ed. Geoffrey

Whittam. London: Collins, 1954. Print.

Dickens,

Charles. Dombey and Son.

Ed. E. A. Horsman and Dennis Walder. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Gaskell,

Elizabeth Cleghorn. Mary

Barton. Ed. Macdonald Daly. London: Penguin, 1996. Print.

My Lady Ludlow

from: Gaskell, Elizabeth Cleghorn. The Cranford Chronicles.

Lexington, KY: Seven Treasures Publications, 2010. Print.

Marryat, Florence. The Blood of the Vampire. Ed.

Greta Depledge. Brighton: Victorian

Secrets, 2010. Print.

Marsh,

Richard. The Beetle: A Mystery.

Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 2007. Print.

Find for free on Kindle: Maurier,

George du. The Martian.

eBook.

“The Adventures of the Resident Patient” from: Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Mysterious Adventures of

Sherlock Holmes. New York: Puffin, 1995. Print.

Find for free on Kindle:

Trollope, Anthony. The Belton

Estate. eBook.

Hi Alastair, your blog really made me laugh - particularly the moustache joke. It is obvious that you have done a lot of research for this piece from your work cited list, and it defiantly comes across in your writing. Reading this made me thankful that I am not a Victorian, especially the information on Nietzsche.

ReplyDeleteSnap with the use of Fuseli! I also came across sleep paralysis whilst I was doing my own research, as some believed that witches haunting peoples dreams caused the paralysis - it is also known as 'Hag Riding', did you come across this in your research too?

Hi Sydney,

ReplyDeleteYeah, Nietzsche had a pretty grim time of it. I came across hag-riding also. If I remember rightly, Night-hag replaced nightmare as the definition for sleep paralysis as the meaning of nightmare broadened over time. Also, the name "Hagrid" in Harry Potter came from the Night-hag. To look "Hag-ridden" means looking rough, so Hagrid took on this name due to his untidy appearance.

Thanks for you comment!